We (collectively) have learned so much about Covid-19 and its causal virus SARS CoV2 in the past three years, but we (individually) know so little. Over 25,000 Covid studies have been pre-printed on medRxiv and bioRxiv. But we struggle even with the little that we know. It seems every bit of new information confuses us. Initially, we seemed to understand about the little spiked balls we saw depicted and thought we understood how those “spikes” can latch onto our cells, but then it turned out there were variation of spikes, indeed, many variations, and then sub-variants; so that by now we can’t even remember which sub-variant is floating around us (Omicron BA.1.1 or Omicron BQ.1.1 or what?). They are all just little spiked balls to us. We prefer things to remain the same. It’s how we are, which is why we talk about returning to the norm or a new norm, as if every moment were not the norm for that moment and always new.

Collectively, humans have learned and done so much during our relatively short time on earth. Yet, individually, human minds are so limited. In the 1950s, the psychologist George Miller wrote a stunning article called “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two” in which he showed that our short term memories held about seven bits of information comfortably but become confused above that. [I imagine it’s even less for old people like me.] For example, if you are shown ten random numbers, unless you are extraordinary, you won’t be able to recited them back, unless you start grouping the numbers in clusters, i.e. reducing the bits of information. You can more easily remember telephone numbers [seven by design?] by registering to yourself, “6, 42, 80, 32” – as people in Mexico do – rather than “6, 4, 2, 8, 0, 3, 2” –as we do here. Clustering is fine with numbers, but not so fine with facts and ideas. We clustered the details of vaccine effectiveness into the simple, mistaken idea that vaccines will keep us Covid free. We turn the statistical notion that outdoor socializing is less risky into the simplistic and wrong idea that we can’t pass our viruses to others outdoors because the wind will blow it away. [Might it not blow it all in someone’s face?]

Because we have long recognized our individual mental limitations, we have devised other ways of keeping track of things we need to consider: pencil and paper, writing, mathematics, categorization, etc., and, recently, machines to keep track of things we cannot remember. Still, the world of big data, even when synopsize by statistics and reduce by averaging, gives too much information for us to factor into our thinking at any one time when we try to think on our feet; so our snap judgments are not too trustworthy.

But many times, even if we are trying to make reasonable choices, according to psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow), we depend on a primitive mental habit of decision-making left over from once having to make quick and decisive acts for survival. We keep using this fast, intuitive, and conclusive leap of judgment to avoid complex thought apparently because we instinctively take the easy and shortest route to a certainty as a means of saving energy. Here is one example of our propensity for jumping to a quick conclusion: If a bat and ball cost $1.10, and the bat costs $1 more than the ball, how much does the ball cost? Most people will say, wrongly, 10 cents (as I did before I thought about it). That’s fast think.

As Kahneman repeatedly shows, fast thinking is biased, easily misled, irrational, and error prone. Fast thinking Covid has been disastrous. For example, Kahneman (with Amos Tversky) found that we are averse to taking risks for a gain if there is a certain loss. This bias would explain how we “fast thought” our way to an aversion of isolation in all its forms – masks, social distancing, and quarantine with its attendant testing and tracing – because it causes a certain loss (money, as well as habits, social life and fun, companionship, etc.), whereas its gain (saving lives) is only potential.

Kahneman’s book had such popular reception because we all recognize these mental errors. Just today a friend told me her partner was thinking of going on a cruise and was advised by his doctor not to worry about Covid because the Omicron strain has less serious symptoms. This expert response falls under Kahneman’s rubric of “answering an easier question” in light of the mortality rate of 100,000 dead a year: it’s a true enough fact that doesn’t take into consideration the patient’s age or his recent chemotherapy treatment for cancer and their effect upon his risks. It avoids having to calculate what his risks actually are. We try to avoid mathematics if we can, and we always can.

Given Miller’s and Kahneman’s demonstrations of our hard wired limitations and given the fact that almost all thinking about Covid is done on our feet without pencil and paper or other aids – unless we are virologists or epidemiologist or statisticians – we see the outlines of how we fast thought our way to this impasse we are in, living through an epidemic but acting as if it didn’t exist. I will fill in this outline in the next Assaying Entropy, which will continue my discussion of Kahneman and will begin:

We prefer the quip to the argument, the repartee to the discussion, certainty to doubt, and, to satisfy that desire, we latch onto falsehoods, half-truths, or irrelevant truths, and we think by associations and intuitions rather than laboriously by reason. But if these limitations were universal, we would see Covid deaths in similar proportions across the globe. But the death rates are wildly different among nations.

In the meantime, think about something Voltaire said: “Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is an absurd one.”

It’s been a looong time since I read the Kahneman book but I do recall when finishing it having a sense how important the results of the studies would be, could be. Taking advantage of a better understanding of the mind might make us take steps to be a better species.

As you say, we gave the book a good reception because we recognize these mental errors. Unfortunately those mental errors are used in so many different ways to manipulate our behaviours.

I look forward to reading your additional takes on “Thinking, fast and slow”.

Thats my 5 cents. Now, can I get a ball?

Thanks, Deb. It is somewhat ironic, isn’t it, that our acceptance of Kahneman’s thesis is based on the fast think mode of anecdotal evidence rather than laboriously checking his procedures?

Your mention of using our mental shortcomings to manipulate our behavior, however, takes us to a second derivative problem. One of Tversky’s and Kahneman’s studies showed that framing the very same problem in different ways affected how people chose to solve that problem [A. Tversky, D. Kahneman, Science 211 (1981) 453–458]. The framing effect was widely accepted as a truth. However, when you take that kind of finding not as intended, as knowledge about ourselves, but use it to manipulate behavior (as advertising does), things can go wildly out of whack because of unintended consequences. Thus, I think the government’s deliberate framing of Covid in terms of how the public perceived it did not help us, as a society, to cope with the epidemic.

As an aside, an example from that study became rather famous as the “Asian disease” problem. In this experiment, which was done almost half a century ago, the story is about something very like Covid. Tversky and Kahneman found that if you frame the response to the epidemic in terms of people dying, solutions avoided risk, but if you framed the response in terms of lives saved, solutions accepted risk.

As for the balls, they are out of stock.

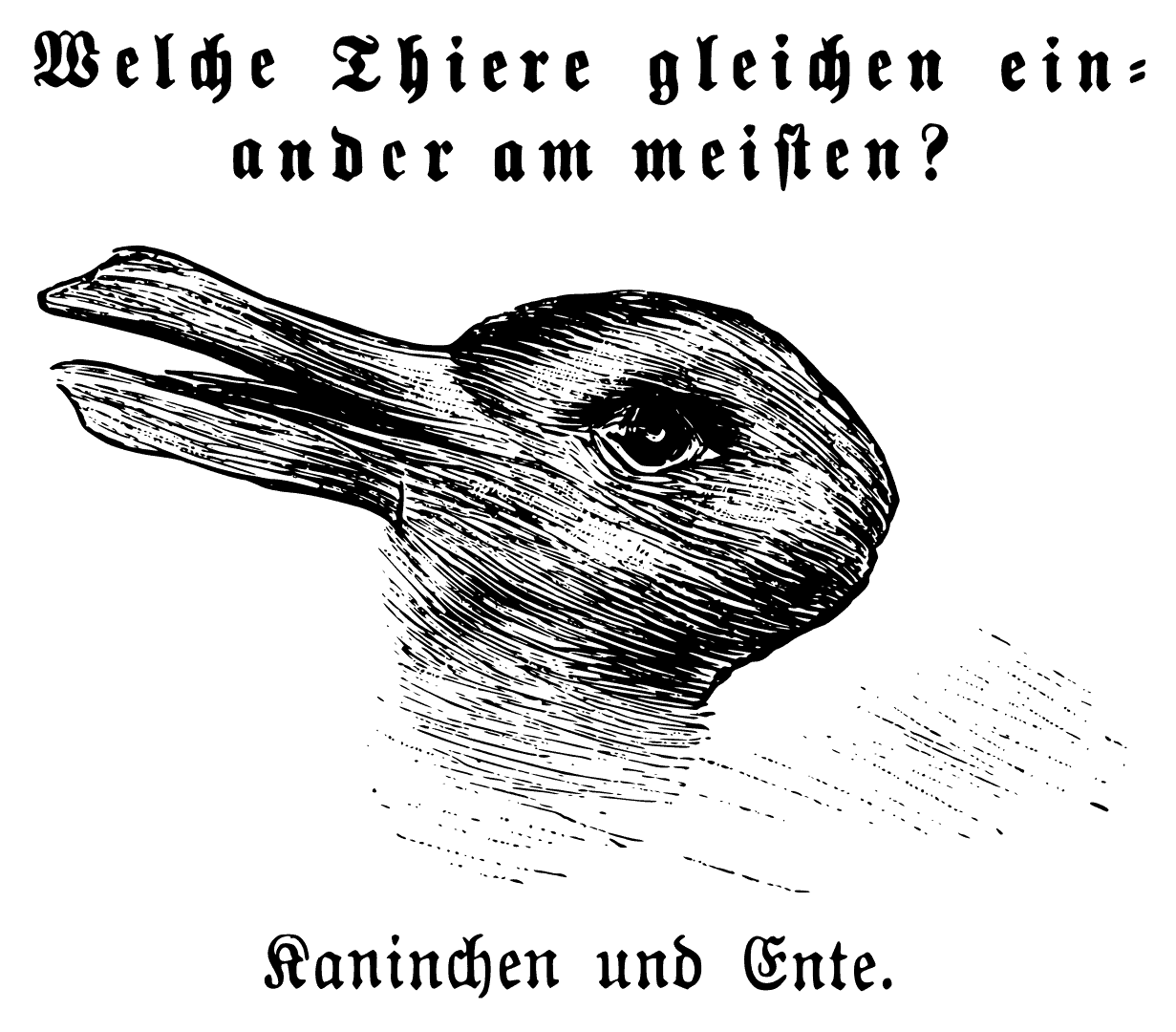

I should explain a bit about the rabbit/duck image I used. We can see the image as either a rabbit or a duck. Most people can switch back and forth between rabbit and duck. A few people can’t switch and see only the rabbit or the duck. No one, as far as I know, can see the image as rabbit and duck at the same time, which, is, of course, the reality. I use this image to support Kahneman’s thesis that the fast thinking habit of jumping to conclusions is hard wired, something we might not have much control over. Our mental limitations are not always a matter of choice. What we can chose is recognition of our limitations and finding workarounds.