Joseph Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953, threw a kink into the plan to kill Joseph “Tito” Broz the next month. Josif Grigulevich and Laura Araujo’s impersonation of Teodoro B. Castro and Inelia Idalina del Puerto Nieves had all been a charade to set up the assassination.

One plan called for Grigulevich to release plague bacteria while he was alone with Tito. Grigulevich would be immunized. But immunization wasn’t 100 percent. Another plan called for poisoning Tito while releasing tear gas to cause panic that would allow Grigulevich to escape. Both sounded like suicide missions. Castro was to sign a letter to his wife, saying he did it because he hated communism — taking the onus off the Soviet Union.

Fear of dying wasn’t his only reservation. Grigulevich liked the man who had led Yugoslavian partisans in their guerrilla war against Germany and now was shepherding an independent socialist country. Tito also liked the young diplomat, though he suspected an ulterior motive. After each meeting, Grigulevich would write one report for his Costa Rican bosses and another to those in Moscow.

Tito’s assassination soon was forgotten as the top brass at Soviet intelligence jockeyed for position as Nikita Khrushchev began his “de-Stalinization.” Three of Grigulevich’s former bosses were arrested. Pavel Sudoplatov, Grigulevich’s spymaster, was imprisoned for 15 years. Leonid Eitingon, who directed the Trotsky campaign, was jailed for 11 years. Lavrently Beria, overall chief of “the Center,” as the headquarters for all intelligence services was called, was executed before 1953 ended.

This was the state of Soviet intelligence when Grigulevich reached Moscow. His first impression was entrenched Russian antisemitism. One general seemed disgusted to be dealing with a Jew. Others didn’t appreciate his unorthodox ways, like mixing professional duties with personal affairs, and his fame as a diplomat. An old acquaintance from his street-fighting days in Lithuania was now the Polish ambassador to Italy. If he recognized the Costa Rican ambassador, the cover would be blown. Alexander Orlov, his chief in Spain, was now a defector in the West and rumored to be writing a book that might name Grigulevich.

At age 40, Grigulevich’s career as a secret foreign agent was over. Nevertheless, he was safe if he kept his past a secret. Laura and Nadezhda joined him in Moscow. In some ways, it must have been a relief no longer to face “fear of possible repercussions for not doing something, for not fulfilling an order,” as he told a Russian interviewer later. He got medals, a pension and an apartment in Moscow. But no job. His forays into the job market and professional societies were stymied because he couldn’t say what he had been doing for the past 20 years. When he suggested to the Center that he approach an old acquaintance, now a prominent politician in a South America country visiting Moscow, about becoming a Soviet intelligence source, he was told to forget it.

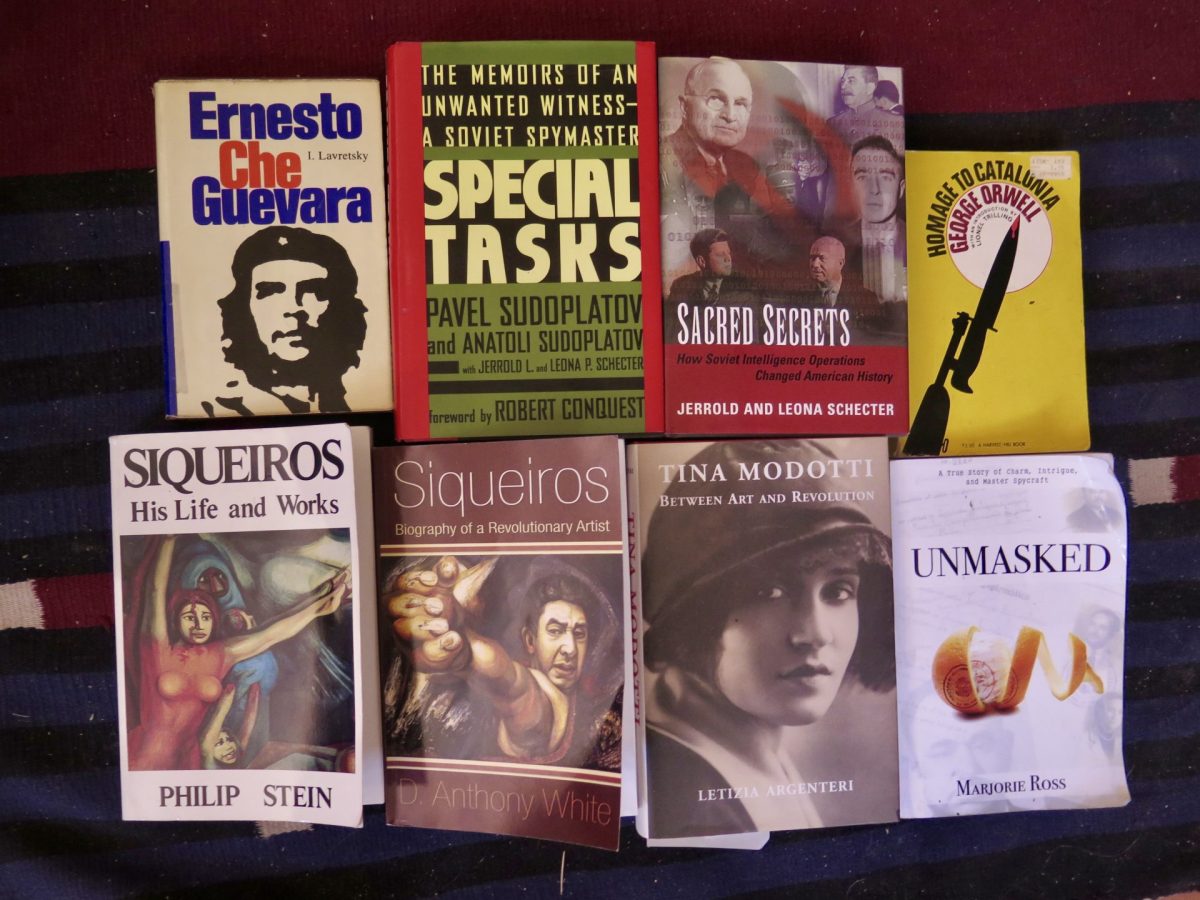

Laura found work as a translator in the KGB’s disinformation bureau. Josif began to write about Latin America and the Vatican. His first published book was a 1957 biography of the 19th century South American liberator Simón Bolivar, with a prologue by his old friend, the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. He also published a biography of David Siqueiros, though he did not to mention their connection. Grigulevich used pseudonyms on his more than 50 books in Russian, usually I. Lavretsky. They were popular with young Soviets curious about the world but usually restricted from traveling abroad. This success brought Grigulevich recognition in academia. He ws declared an Emeritus of Science, joined the history department of the Institute of Ethnography, was appointed to the USSR Academy of Sciences and served as editor in chief of the journal Social Sciences.

Grigulevich’s only book translated into English, and consequently the only one I have read, is a 1976 biography of the Argentine medical student turned Cuban revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara. It’s a hagiography without critical analysis, coming nine years after Che was killed in Bolivia, with bits of Marxist analyses and personal comments about his time in the Spanish Civil War. But he never published a first-hand account of his life as a secret agent. He was known to joke that the world is run by spies, prostitutes and journalists.

Grigulevich died on June 2, 1988, at age 75. The next year, the Berlin Wall came down and perestroika began. The Soviet Union dissolved at the end of 1991. Laura died in 1997. Nadezhda taught at a college in Omsk, in southern Siberia, where she specialized in ethno-ecology, history and ethnography of the peoples of the North and South Caucasus. Over the past decade, I have sent her messages, in English and Russian, via social media and direct email. She has never responded. One recent report has Nadezhda, 72, living in the family apartment in Moscow with a younger brother. In an interview with a Russian reporter, she said her father never spoke to her about being a secret agent. Her main memory is him bent over his writing desk. “He had nothing else in life,” she said. “No hobbies. No entertainment. Reading was his recreation.”

Sources:

Ernesto Che Guevara by I. Lavretsky (a pseudonym). Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1976

The Illegals: Russia’s most audacious spies and their century-long mission to infiltrate the West by Shaun Walker, published in April 2025, is the newest book to mention Grigulevich. He is cited as an example of an “illegal,” a type of spy with a long history in Russia — dating back to the Bolshevik underground in czarist times. My only quibble is its assertion that Grigulevich met Laura Aruajo in South America where she was already a Soviet agent. Other sources indicate he met her in Mexico City during the Trotsky caper and that they left Mexico together.

This is the final installment of an 11-part series on Josif Grigulevich.

Very nice series and as a long-time student of Soviet history and spying I found it a fine use of the Citizen’s platform.

Editing could have been better (Grigulevich was spelled in many different ways, Beria’s first name transliteration is Lavrentiy, etc.). Photo source citations would have been welcome.

Nice work!

Thanks, Tom, for a thoroughly interesting and intriguing piece. I like especially the distance you put between yourself and your topic — reporterly — which frees the topic from judgmental politicization that is so easy to do when it comes to the history of the Soviet Union.