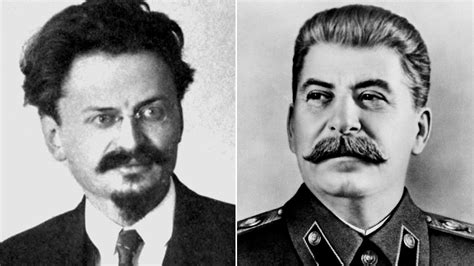

The Spanish Civil War was a trial by fire for Josif Grigulevlich. Not only did he learn about celebrity journalism and assassination, he got a first-hand glimpse how the political left was split between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky. Grigulevich had been a child when Stalin stripped Trotsky of his Soviet positions, exiled him and had his name and images removed from official histories. When he arrived in Spain in early 1936, Trotsky was living in Turkey. But Stalin’s disinformation machine blamed Trotsky and his acolytes for train derailments and factory fires in Russia.

Vladimir Lenin’s closest associate after the 1917 revolution, Trotsky called for “perpetual revolution” with communism sweeping the globe and national governments withering away — a version of socialism that seemed closer to Karl Marx’s ideal and more palatable in the West. Stalin, who took power after Lenin’s death in 1924, found Trotsky’s internationalist philosophy unrealistic and dangerous for the Soviet Union and himself. He pledged instead to “perfect socialism in one country at a time.”

The Spanish Civil War, 1936-39, pitted the Republicans, made up of left-wingers, anarchists, anticlericals, trade unionists and Catalonian separatists, against the Nationalists, made up of traditional conservatives, royalists, loyal Roman Catholics and elements of the military. The Nationalists were led by General Francisco Franco with materiel support from Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy.

A main Republican militia was the POUM (Spanish abbreviation for Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification), a coalition of Spanish leftists and democratic socialists from Europe and the Americas, including the Lincoln Brigade from the United States. The Soviet Union supported the Republicans and the POUM, but Stalin secretly sent along an NKVD (Russian abbreviation for Peoples’ Commissariat for State Security) assassination team. The NKVD began as a border patrol, but under Stalin targeted anyone anywhere deemed a threat to the Soviet Union. In Spain, that meant the POUM’s leader, Andreu Nin Pérez, a Trotsky supporter. In late June of 1937, the NKVD team captured Nin, tortured him to try to make him confess he had been in cahoots with the Nationalists, and finally killed him. That job fell to the youngest team member, Grigulevich, 24, known as Felipe or “the French Jew.” Nin’s body was never found. NKVD teams carried portable crematories.

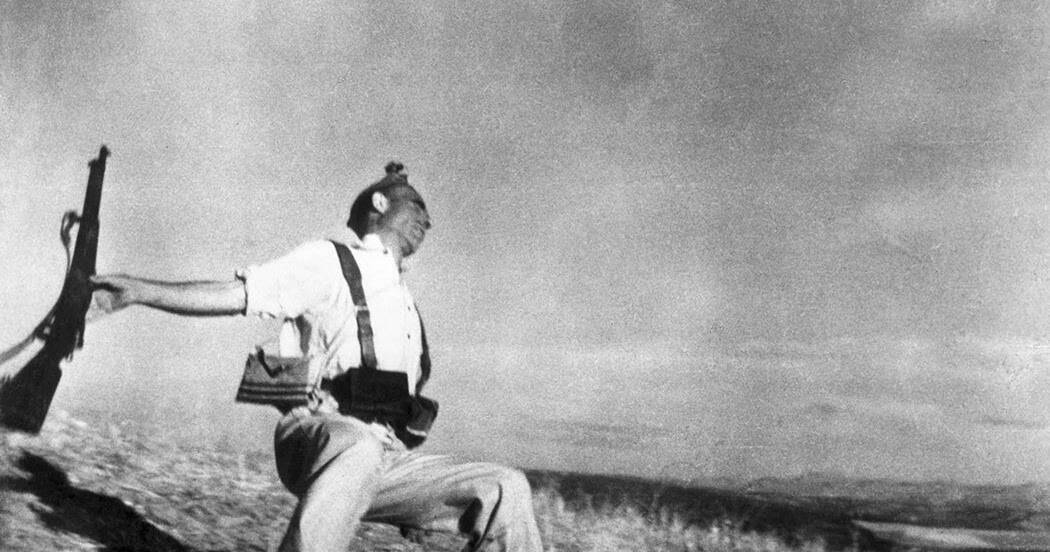

The Spanish Civil War also introduced Grigulevich to propaganda, disinformation and celebrity journalists. Among those who crossed his path were Ernest Hemingway who rushed from one trench line to another and whose novel For Whom the Bell Tolls romanticized the Spanish Republican cause, Hemingway’s third wife Martha Gelhorn who covered for Collier’s Weekly and photographer Robert Capa whose image of a soldier falling from a head shot became the war’s most celebrated photo, even though some claimed later it was faked.

The relatively unknown English writer Eric Blair came to Spain to cover the war, but was so taken by the Republican cause that he joined the POUM militia. As he recuperated from a sniper’s bullet to his neck, he began to understand how the term Trotskyite had become a slur aimed at influencing public opinion. “`Trotskyism’ only came into public notice in the time of the Russian sabotage trials, and to call a man a Trotskyist is practically the equivalent of calling him a murderer, agent provocateur, etc. But at the same time anyone who criticizes Communist policy from a Left-wing standpoint is liable to be denounced as a Trotskyist,” he would later write under his pen name George Orwell.

Because Grigulevich spoke fluent Spanish, some in Spain assumed he was with the Mexican brigade. Its most famous member was the artist, war hero and union organizer David Siqueiros who had come to Spain with the intent of making murals but ended up, like Blair/Orwell, joining the armed struggle. As the Nationalists overpowered the Republicans, Stalin ordered the elimination of “the last Trotskyite,” Trotsky himself, in exile in Mexico. Siqueiros was already there. NKVD team leader Alexander Orlov and Grigulevich were summoned to Moscow. Expecting the worst, Orlov fled for Canada. So overall control of “Operation Duck” went to another NKVD agent in Spain, Naum Eitingon. Grigulevich agreed to meet up with them in Mexico.

Sources:

Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1938.

Three Who Made a Revolution by Bertram D. Wolfe, Beacon Press, 1948.

Stalin’s Agent: The Life and Death of Alexander Orlov by Boris Volodarsky , Oxford University Press, 2016.