This is the second in a series of three articles about the New Mexico Veterans Home. The third focuses on the old hospital building, now mostly empty. All photos courtesy of the Geronimo Springs Museum. See Part One See Part Three

One of Sierra County’s biggest industries — first Carrie Tingley Hospital for Crippled Children, now the New Mexico State Veterans Home — got started more than 90 years ago due to FDR’s polio.

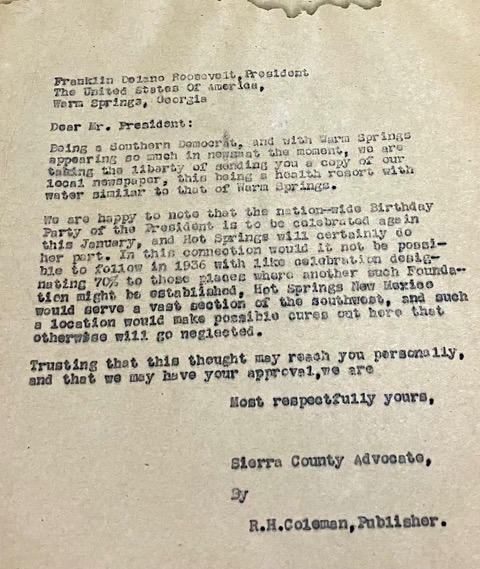

On November 26, 1934, the publisher of the Sierra County Advocate wrote to Franklin Delano Roosevelt to suggest that the thermal waters of the town then called Hot Springs, New Mexico, should be used to treat what was then known as infantile paralysis. Creating a charitable foundation here like Roosevelt had done in Georgia “would make possible cures out here that otherwise will go neglected,” wrote R.H. “Bob” Coleman.

The letter, now in the files of Geronimo Springs Museum, was sent not to the White House in Washington, D.C., but to the president’s semi-secret retreat in Warm Springs, Georgia, without mentioning why Roosevelt might have been there.

Roosevelt’s legs had been paralyzed since the summer of 1921, when he was 39. After hearing of cures from hydrotherapy, the scion of the wealthy and politically connected New York family purchased the Georgia springs, a nearby inn and surrounding farm. He created a foundation to run a children’s clinic there that eventually became the March of Dimes. He visited often and died there in 1945.

Roosevelt learned to walk with metal braces and help from aides. He gave speeches standing alone at a securely fixed dais, grasping it with both hands and gesturing emphatically with his head — a move his fans found appealing. His upper body grew muscular from frequent swimming and other exercise. With encouragement from his wife, the Democrat, former state senator and losing 1920 vice-presidential candidate, reentered politics. In 1928, he was elected governor of New York. In 1932, he was elected president in a landslide, launched a period of unprecedented government growth and went on to be reelected an unprecedented three times.

Yet most Americans remained unaware of Roosevelt’s condition. He hid it, thinking the public would see disability as a political liability. The media went along in a “friendly conspiracy” unlikely today. Newspapermen ignored the president’s disability under threat that reporting it would mean losing access. Anyone trying to photograph him in his wheelchair risked the Secret Service seizing their cameras and destroying their film. As World War II loomed, keeping the president’s condition a secret was framed as a matter of national security.

Coleman, however, knew about FDR’s disability and his Georgia retreat — probably via Gov. Clyde Tingley, an enthusiastic supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal and an advocate for better healthcare. His wife Carrie’s tuberculosis had brought them to New Mexico decades earlier. Soon after he was elected governor and Roosevelt president in 1932, Tingley began looking to build a state hospital for children crippled by polio. During a visit to Hot Springs, he mentioned that the bluff overlooking downtown would be an ideal site. Coleman wrote about the comment and began looking to acquire the property known as “Newman’s Camp.” The initial dealings are detailed in letters, press releases and other documents in the files of Geronimo Springs Museum.

In a Jan. 3, 1935, letter, Coleman told Tingley the landowner, E.V. Newman, told him “he would do `just what he told you he would do.’ So that clears up that situation.” Soon, Coleman and three other men telegrammed Tingley to say they had secured 430 feet of highway frontage with acreage on the bluff and a site for a hot-water well in the flats. Locals raised $12,000 to buy the land and donated it to the state. Tingley estimated the new hospital, to be named for his wife, would cost $300,000 with the state putting up no more than $25,000. Ultimately, construction was about $827,000 — $553,000 from the U.S. Works Progress Administration and $273,000 from the state. Fully equipping the new hospital brought the total to about $1 million — more than $27 million in today’s dollars.

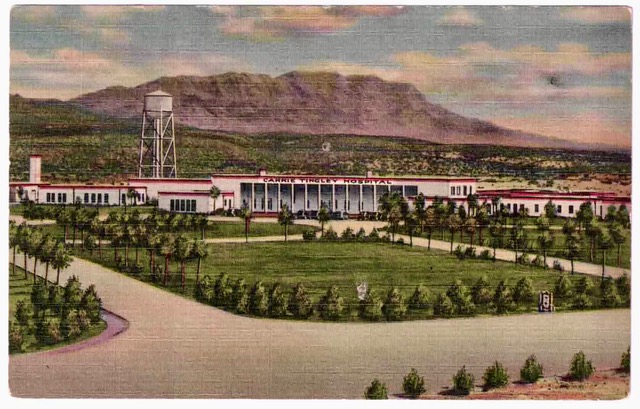

Construction began in early 1936 and continued through the summer of 1937, with labor by the Civilian Conservation Corps and bricks called “pen tile” made at the state penitentiary in Santa Fe and hauled to Hatch by the Santa Fe Railroad. State architect William Kruger, in consultation with the architect of the Warm Springs clinic, designed the sprawling building in the Territorial Revival style with stucco plaster, a flat roof and decorative brick cornice. It had 100 beds in dormitory-style rooms with windows facing outside or into large courtyards, to give patients direct access to fresh air and sunshine. It also had a shop that made braces and prosthetics and a physical therapy room with a 35,000-gallon pool fed by thermal water pumped from a well downtown. FDR never got to soak there, but a bronze plaque in the hospital’s common room says the project was “aided by the sympathetic interest of” Roosevelt.

On September 1, 1937, Carrie Tingley Hospital for Crippled Children began accepting patients. The press ate up the story. “Crippled tots given haven,” headlined The El Paso Times. The Santa Fe New Mexican reported the hospital’s iron lung was keeping alive a 24-year-old man from Los Angeles. A few weeks later, The Silver City Press reported the man had died. Through the 1930s and ‘40s, the hospital thrived as a regional center for polio and other childhood maladies and an international training ground for orthopedic surgery and therapies. A 1939 report said 32.3 percent of its patients were treated for poliomyelitis, 19.2 percent for congenital defects, 11.4 percent for osteomyelitis (a bone infection), 9.5 percent for traumatic defects, 9.3 percent for spastic paralysis, 6.7 percent for tuberculosis, 5.6 percent for arthritis and 5.6 percent for miscellaneous ailments. After Hot Springs changed its name to Truth or Consequences in 1950, the radio game show’s emcee Ralph Edwards made the hospital a regular stop in his annual visits with Hollywood celebrities in tow.

Carrie Tingley Hospital continued to use hydrotherapy and so-called passive exercises in the hot mineral water, even as some questioned the efficacy for paralysis and swimming pools were found to be a vector of transmission of the polio virus. As vaccines began to eradicate polio in 1954, the hospital focused other diseases like muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy and scoliosis. The late Rudolfo Anaya, who was treated there in the summer of 1954 for a spinal cord injury, later wrote a novel, Tortuga, about a disabled boy in such a hospital, derided for moving like a tortoise. In a 1977 section commemorating the hospital’s 40th year, the Sierra County Herald defended water therapy as “necessary for the healing of orthopedic disorders. Children who cannot walk on land often find movement in water easer. Even those who must be physically lowered into the pool find they can achieve some degree of motion and relief from pain in the steaming 110 degree mineral water.”

On June 12, 1981, the hospital closed, citing difficulty in finding qualified medical staff in Truth or Consequences. Patients and some staff were relocated to a new building in Albuquerque, near the University of New Mexico Hospital, where Carrie Tingley Hospital continues to operate today. The original hospital remained vacant while state officials fielded proposals to buy the property, then appraised at $1.2 million. After rejecting an El Paso hotelier’s offer of $900,000 to use it for a health spa, state officials endorsed a plan to turn the building into New Mexico’s first and only retirment home for military veterans. The U.S. Veterans Administration pledged to pay 65 percent of the remodeling costs. The state legislature approved a $3.7 million in 1984 and remodeling began on the 186-bed veterans home.

On Nov. 11, 1986, every member of New Mexico’s Congressional delegation attended the grand opening of the New Mexico State Veterans Center. In 2017, the renamed New Mexico Veterans “Home” added a 59-bed facility called “The Annex” for people with dementia and others who just prefer more security. The Annex has a small theater, an exercise room, a one-lane bowling alley and an indoor swimming pool. A resident of one of the new units recently began showing films in the Annex theater two nights a week. The exercise room and its equipment look seldom used. The bowling alley and the swimming pool have never been used. At one time, the home looked into using thermal water from its well. But that was never done, and when city water was used to fill it, freeze-damaged pipes, leaks and other plumbing problems were discovered. For a time after the hospital closed, locals were allowed to use its hot-water pool. But it has remained unfilled for decades. So the property currently has two non-working pools. The water tower, the highest structure on the low-profile campus, also appears to be nonfunctioning.

I was told recently that the annex is where they house dementia.how can a bowling lane,swimming pool and what ever else might be in there.The annex has 112 rooms from level and level 2 .for patients with dementia.they have their own bathrooms etc .so how is it that all the added is there? It has a 112 bedrooms .and someone showing movies now.would that be on which. Level at annex ?

Also yes the Governor put 60 million in for new buildings but already the laundry machines and dish washers are breaking down ? Is that out of the 60 million ? To buy cheapy made laundry & dishwashers for the new Vet buildings that cost 60 million??

Once again, Tom has given us a well-researched and well written article. Learned much about the Tingley Hospital and the Veterans Home. Thanks!

Once again Tom has impressed me with his well-researched and written article. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

A little FYI, my friend, who was not sick, used the pool around 2008.

Thanks for a great article!